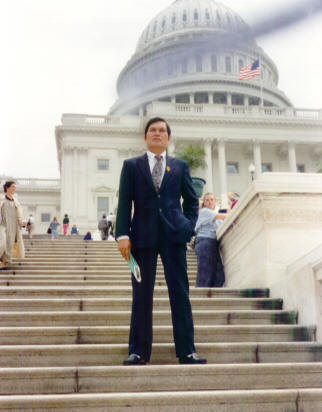

at Capitol. June 19.1996

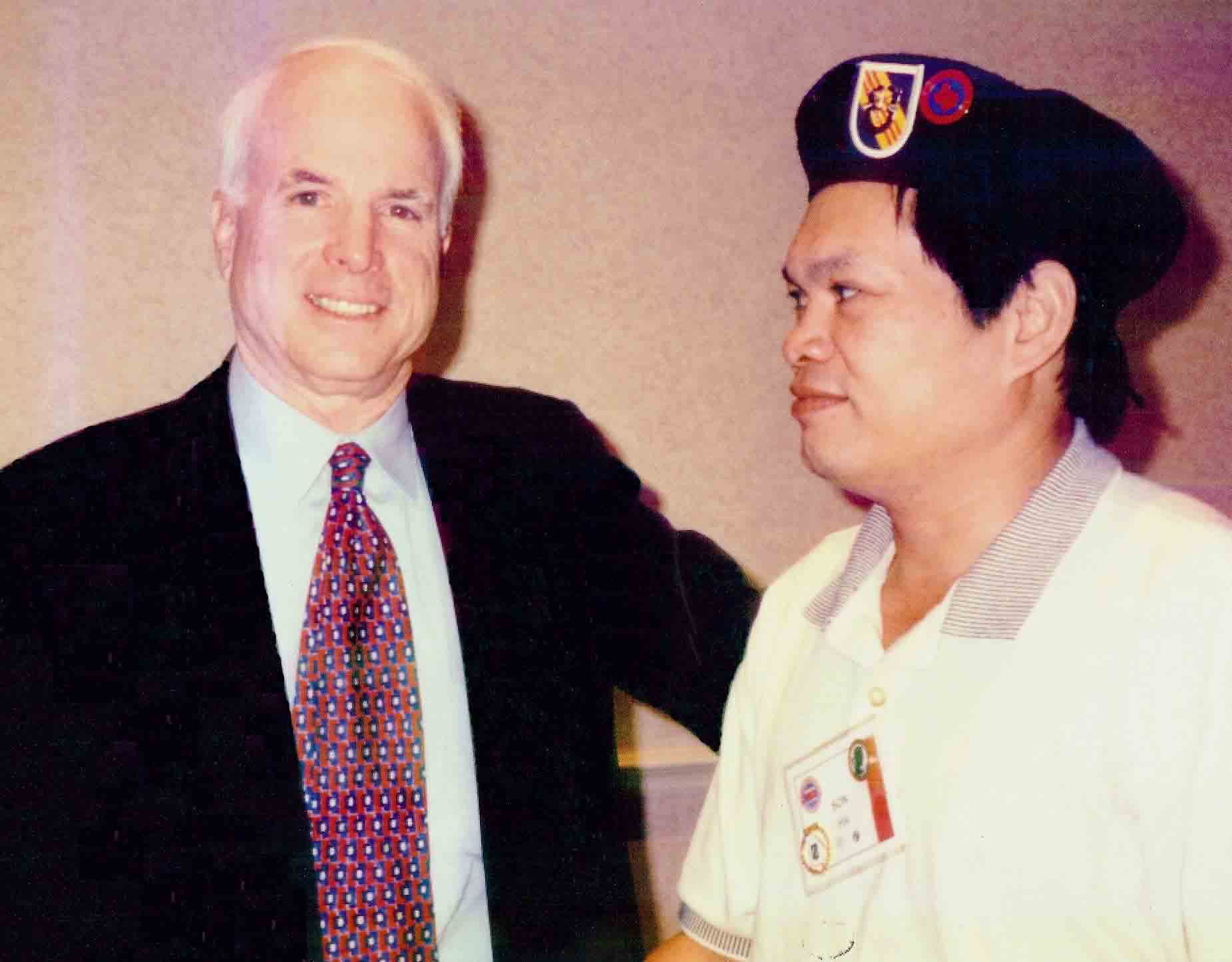

with Sen. JohnMc Cain

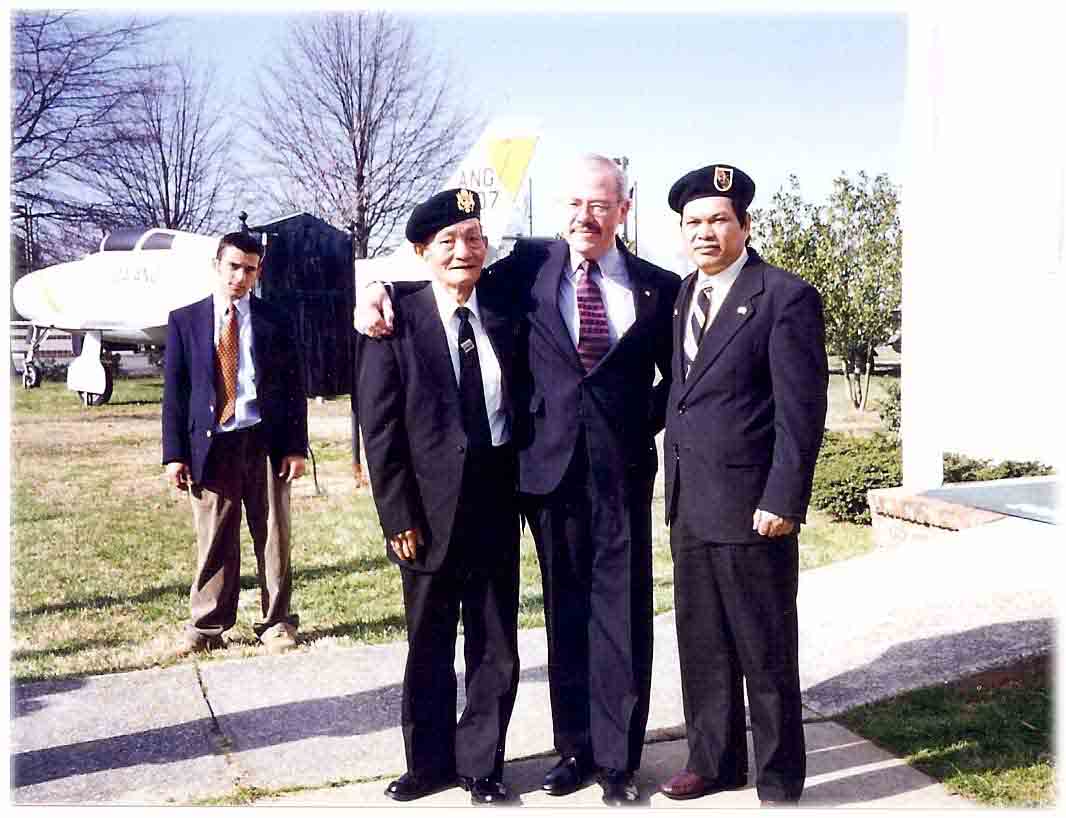

with General John K Singlaub

CNBC .Fox .FoxAtl .. CFR. CBS .CNN .VTV.

.WhiteHouse .NationalArchives .FedReBank

.Fed Register .Congr Record .History .CBO

.US Gov .CongRecord .C-SPAN .CFR .RedState

.VideosLibrary .NationalPriProject .Verge .Fee

.JudicialWatch .FRUS .WorldTribune .Slate

.Conspiracy .GloPolicy .Energy .CDP .Archive

.AkdartvInvestors .DeepState .ScieceDirect

.NatReview .Hill .Dailly .StateNation .WND

-RealClearPolitics .Zegnet .LawNews .NYPost

.SourceIntel .Intelnews .QZ .NewAme

.GloSec .GloIntel .GloResearch .GloPolitics

.Infowar .TownHall .Commieblaster .EXAMINER

.MediaBFCheck .FactReport .PolitiFact .IDEAL

.MediaCheck .Fact .Snopes .MediaMatters

.Diplomat .NEWSLINK .Newsweek .Salon

.OpenSecret .Sunlight .Pol Critique .

.N.W.Order .Illuminatti News.GlobalElite

.NewMax .CNS .DailyStorm .F.Policy .Whale

.Observe .Ame Progress .Fai .City .BusInsider

.Guardian .Political Insider .Law .Media .Above

.SourWatch .Wikileaks .Federalist .Ramussen

.Online Books .BREIBART.INTERCEIPT.PRWatch

.AmFreePress .Politico .Atlantic .PBS .WSWS

.NPRadio .ForeignTrade .Brookings .WTimes

.FAS .Millenium .Investors .ZeroHedge .DailySign

.Propublica .Inter Investigate .Intelligent Media

.Russia News .Tass Defense .Russia Militaty

.Scien&Tech .ACLU .Veteran .Gateway. DeepState

.Open Culture .Syndicate .Capital .Commodity

.DeepStateJournal .Create .Research .XinHua

.Nghiên Cứu QT .NCBiển Đông .Triết Chính Trị

.TVQG1 .TVQG .TVPG .BKVN .TVHoa Sen

.Ca Dao .HVCông Dân .HVNG .DấuHiệuThờiĐại

.BảoTàngLS.NghiênCứuLS .Nhân Quyền.Sài Gòn Báo

.Thời Đại.Văn Hiến .Sách Hiếm.Hợp Lưu

.Sức Khỏe .Vatican .Catholic .TS KhoaHọc

.KH.TV .Đại Kỷ Nguyên .Tinh Hoa .Danh Ngôn

.Viễn Đông .Người Việt.Việt Báo.Quán Văn

.TCCS .Việt Thức .Việt List .Việt Mỹ .Xây Dựng

.Phi Dũng .Hoa Vô Ưu.ChúngTa .Eurasia.

CaliToday .NVR .Phê Bình . TriThucVN

.Việt Luận .Nam Úc .Người Dân .Buddhism

.Tiền Phong .Xã Luận .VTV .HTV .Trí Thức

.Dân Trí .Tuổi Trẻ .Express .Tấm Gương

.Lao Động .Thanh Niên .Tiền Phong .MTG

.Echo .Sài Gòn .Luật Khoa .Văn Nghệ .SOTT

.ĐCS .Bắc Bộ Phủ .Ng.TDũng .Ba Sàm .CafeVN

.Văn Học .Điện Ảnh .VTC .Cục Lưu Trữ .SoHa

.ST/HTV .Thống Kê .Điều Ngự .VNM .Bình Dân

.Đà Lạt * Vấn Đề * Kẻ Sĩ * Lịch Sử *.Trái Chiều

.Tác Phẩm * Khào Cứu * Dịch Thuật * Tự Điển *

KIM ÂU -CHÍNHNGHĨA -TINH HOA - STKIM ÂU

CHÍNHNGHĨA MEDIA-VIETNAMESE COMMANDOS

BIÊTKÍCH -STATENATION - LƯUTRỮ -VIDEO/TV

DICTIONAIRIES -TÁCGỈA-TÁCPHẨM - BÁOCHÍ . WORLD - KHẢOCỨU - DỊCHTHUẬT -TỰĐIỂN -THAM KHẢO - VĂNHỌC - MỤCLỤC-POPULATION - WBANK - BNG ARCHIVES - POPMEC- POPSCIENCE - CONSTITUTION

VẤN ĐỀ - LÀMSAO - USFACT- POP - FDA EXPRESS. LAWFARE .WATCHDOG- THỜI THẾ - EIR.

ĐẶC BIỆT

-

The Invisible Government Dan Moot

-

The Invisible Government David Wise

ADVERTISEMENT

Le Monde -France24. Liberation- Center for Strategic- Sputnik

https://www.intelligencesquaredus.org/

Space - NASA - Space News - Nasa Flight - Children Defense

Pokemon.Game Info. Bách Việt Lĩnh Nam.US Histor. Insider

World History - Global Times - Conspiracy - Banking - Sciences

World Timeline - EpochViet - Asian Report - State Government

https://lens.monash.edu/@politics-society/2022/08/19/1384992/much-azov-about-nothing-how-the-ukrainian-neo-nazis-canard-fooled-the-world

with General Micheal Ryan

3

CENTRAL PERSONNEL AGENCIES:

MANAGING

THE

BUREAUCRACY

Donald

Devine,

Dennis Dean Kirk, and Paul Dans

OVERVIEW

From

the

very

first

Mandate for

Leadership,

the

“personnel is

policy” theme

has

been

the

fundamental

principle guiding

the

government’s

personnel management. As

the U.S.

Constitution

makes clear,

the

President’s

appointment, direction,

and

removal

author-

ities

are

the

central elements

of

his

executive power.1 In

implementing

that power,

the

people and

the President

deserve the

most talented

and

responsible workforce possible.

Who

the

President

assigns to

design and

implement his

political policy

agenda will

determine whether he

can carry

out the

responsibility given to

him by

the American

people.

The

President

must

recognize

that

whoever

holds

a

government position

sets

its

policy.

To fulfill

an

electoral

mandate,

he

must

therefore

give

per-

sonnel

management

his

highest

priority, including

Cabinet-level

precedence.

The

federal government’s

immense bureaucracy

spreads into

hundreds of

agen-

cies

and

thousands

of

units

and

is

centered and

overseen at

the

top

by

key

central personnel

agencies

and

their

governing laws

and

regulations.

The

major

separate personnel

agencies in

the national government

today are:

•

The

Office of Personnel Management (OPM);

•

The

Merit

Systems Protection

Board

(MSPB);

•

The

Federal

Labor Relations

Authority

(FLRA); and

•

The

Office

of Special

Counsel

(OSC).

Mandate for

Leadership: The Conservative

Promise

Title

5 of

the U.S.

Code charges

the OPM

with executing,

administering, and enforcing

the

rules,

regulations,

and

laws

governing

the

civil

service.2 It

grants

the OPM

direct responsibility

for

activities

like retirement,

pay, health,

training, federal

unionization,

suitability, and

classification

functions

not

specifically

granted to

other

agencies

by

statute.

The

agency’s

Director is

charged with

aiding the

President, as

the

President

may request,

in

preparing

such

civil service

rules

as

the

President

pre-

scribes

and

otherwise

advising

the

President

on

actions

that

may

be

taken

to

promote

an efficient civil service

and a systematic application of the merit system principles,

including

recommending

policies

relating

to

the

selection,

promotion,

transfer,

per-

formance,

pay, conditions

of

service,

tenure,

and

separation

of

employees.

The

MSPB is

the

lead

adjudicator for

hearing and

resolving cases

and

contro-

versies

for

2.2

million federal

employees.3 It

is

required to

conduct fair

and

neutral

case

adjudications,

regulatory reviews, and

actions and

studies to

improve the

workforce.

Its

court-like

adjudications

investigate

and

hear

appeals

from

agency actions

such as furloughs, suspensions, demotions, and terminations and

are appealable to

the U.S.

Court of

Appeals.

The

FLRA hears

appeals of

agency personnel

cases involving

federal labor

griev-

ance

procedures

to

provide

judicial review

with binding

decisions appealable

to

appeals

courts.4 It

interprets

the

rights

and

duties

of

agencies

and

employee

labor organizations—on

management

rights, OPM

interpretations,

recognition

of

labor

organizations,

and

unfair

labor practices—under

the

general

principle of

bargain- ing

in good

faith and

compelling need.

The

OSC

serves

as

the

investigator,

mediator,

publisher, and

prosecutor before

the

MSPB with

respect to

agency and

employees

regarding prohibited person-

nel practices, Hatch Act5

politicization, Uniformed Services

Employment and Reemployment

Rights Act6

issues,

and

whistleblower complaints.7

The

Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission

(EEOC) has

general respon-

sibility

for reviewing charges of

employee

discrimination

against all

civil rights

breaches.

However,

it also

administers

a government

employee

section

that

investi- gates and adjudicates

federal employee complaints concerning equal employment

violations

as with

the

private

sector.8

This

makes

the

agency

an

additional

de

facto

factor in government

personnel management.

While

not

a

personnel agency

per

se,

the

General

Services Administration

(GSA)

is

charged

with general

supervision of

contracting.9 Today,

there

are

many more

contractors in

government than there are civil service employees. The GSA must

therefore

be a

part of

any personnel

management discussion.

ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

OPM: Managing

the Federal Bureaucracy.

At the very pinnacle of the modern

progressive

program to

make

government competent stands

the ideal of

professionalized,

career civil

service. Since

the turn

of the

20th century,

2025 Presidential

Transition Project

progressives have sought a system

that could effectively select, train, reward,

and

guard

from

partisan

influence

the

neutral

scientific

experts

they

believe

are required

to

staff

the

national

government

and

run

the

administrative

state.

Their

U.S.

system was

initiated by

the

Pendleton

Act

of

188310 and

institutionalized

by

the

1930s New

Deal to

set

principles

and

practices

that were

meant to

ensure that

expert

merit rather

than partisan

favors or

personal

favoritism ruled within

the federal bureaucracy. Yet,

as public

frustration with the

civil service

has grown,

generating calls

to “drain

the swamp,”

it has

become clear

that their

project has

had serious unintended consequences.

The

civil service

was

devised

to

replace

the

amateurism

and

presumed

corrup-

tion

of

the

old

spoils

system, wherein

government jobs

rewarded loyal

partisans who

might or

might not

have

professional backgrounds. Although

the system

appeared to be sufficient

for the

nation’s first

century,

progressive intellectuals and

activists

demanded

a

more

professionalized,

scientific,

and

politically

neutral

Administration.

Progressives

designed

a

merit

system

to

promote

expertise

and shield

bureaucrats

from

partisan

political

pressure,

but

it

soon

began

to

insulate

civil servants from

accountability. The modern merit system increasingly made it

almost

impossible

to fire

all

but

the

most

incompetent

civil

servants.

Complying with

arcane

rules

regarding

recruiting,

rating,

hiring,

and

firing

simply

replaced the

goal of

cultivating

competence and expertise.

In the 1970s, Georgia Democratic

Governor Jimmy Carter, then a political

unknown,

ran

for

President

supporting

New

Deal

programs

and

their

Great

Soci-

ety

expansion

but opposing

the

way

they

were

being

administered.

The

policies

were not

actually

reducing

poverty,

increasing

prosperity,

or

improving

the

envi-

ronment,

he argued,

and

to

make

them

work

required

fundamental

bureaucratic

reform. He

correctly charged that

almost all

government

employees were rated

as

“successful,” all

received

the

same

pay

regardless

of

performance,

and

even

the

worst

were

impossible

to fire—and

he

won

the

presidency.

President

Carter fulfilled his campaign promise by hiring Syracuse

University Dean

Alan Campbell,

who

served

first as

Chairman of

the

U.S.

Civil Service

Com-

mission and then as Director of the OPM and helped him devise and pass

the Civil

Service

Reform Act

of

1978

(CSRA)11 to

reset

the

basic

structure of

today’s bureau-

cracy.

A new

performance

appraisal system was

devised with

a five rather

than three

distribution

of

rating

categories

and

individual

goals

more

related

to

agency

missions

and

more

related

to

employee

promotion

for

all.

Pay

and

benefits

were

based

directly

on improved

performance

appraisals

(including

sizable

bonuses)

for mid-level

managers and

senior

executives. But time

ran out

on President

Carter before the act

could be

fully

executed, so it

was left

to President

Ronald Reagan

and his

new OPM

and agency

leadership to implement.

Overall,

the new

law seemed

to work

for a

few years

under Reagan,

but the

Carter–

Reagan

reforms were

dissipated within

a

decade.

Today, employee

evaluation is

back

Mandate for

Leadership: The Conservative

Promise

to

pre-reform levels

with almost

all

rated

successful or

above, frustrating

any

rela-

tion

between

pay

and

performance. An

“outstanding”

rating

should be

required for

Senior

Executive

Service

(SES) chiefs

to

win

big

bonuses,

but

a

few

years

ago, when it was

disclosed that the Veterans Administration executives who

encouraged false reporting of waiting lists for hospital

admission were rated outstanding, the Senior

Executive

Association

justified

it,

telling

Congress that

only

outstanding

performers would

be

promoted

to

the

SES

in

the

first

place

and

that

precise

ratings

were

unnec-

essary.12 The

Government

Accountability

Office

(GAO), however,

has

reported

that pay raises, within-grade pay increases, and locality

pay for regular employees and

executives

have

become

automatic rather

than based

on

performance—as

a

result

of

most

employees being

rated at

similar appraisal

levels.13

OPM:

Merit Hiring

in a

Merit System.

It should not

be impossible

even for

a

large

national

government

to

hire

good

people

through

merit

selection.

The government

did so

for years,

but it

has proven

difficult in recent

times to

select personnel

based on

their

knowledge,

skills,

and

abilities

(KSA)

as

the

law

dictates.

Yet for

the

past

34

years,

the

U.S.

civil

service

has

been

unable

to

distinguish

con- sistently

between strong

and unqualified applicants for

employment.

As the Carter

presidency was winding

down, the

U.S. Department

of Justice

and

top lawyers

at

the

OPM

contrived

with

plaintiffs

to

end

civil

service

IQ

exam-

inations

because of

concern

about

their

possible

impact

on

minorities.

The

OPM had

used

the

Professional and

Administrative

Career

Examination

(PACE)

gen-

eral intelligence exam to

select college graduates for top agency employment, but Carter

Administration officials—probably without the President’s

informed con- currence—abolished

the

PACE

through

a

legal

consent

court

decree

capitulating to

demands

by

civil

rights

petitioners who

contended

that

it

was

discriminatory. The

judicial

decree

was

to

last

only

five

years

but

still

controls

federal hiring

and is

applied to

all KSA tests

even today.

General

ability

tests

like

the

PACE

have

been used

successfully

to assess

the

use-

fulness and

cost-effectiveness of broad intellectual qualities across many

separate occupations.

Courts have

ruled that

even without

evidence of

overt,

intentional discrimination,

such results might suggest discrimination. This doctrine of

dispa- rate

impact

could

be

ended

legislatively or

at

least

narrowed

through

the

regulatory

process by a future

Administration. In any event, the federal government has been

denied

the

use

of

a

rigorous

entry examination

for

three

decades,

relying

instead on

self-evaluations that have forced managers to resort to

subterfuge such as

preselecting

friends

or

associates

that

they

believe

are

competent

to

obtain

qual- ified

employees.

In

2015, President

Barack Obama’s

OPM

began

to

introduce

an

improved

merit examination called USAHire, which it had been

testing quietly since 2012 in a few agencies

for

a

dozen

job

descriptions.

The

tests

had

multiple-choice

questions with

only

one

correct answer.

Some questions

even required

essay replies:

questions

2025 Presidential

Transition Project

that would

change regularly to depress cheating. President Donald Trump’s

OPM planned

to implement such changes

but was

delayed

because of

legal concerns

over possible disparate impact.

Courts

have agreed

to review

the consent

decree if

the Uniform Guidelines

on

Employee

Selection

Procedures

setting

the

technical

requirements

for

sound exams

are reformed.

A government

that is

unable to

select

employees based on

KSA-like

test

qualifications

cannot

work,

and

the

OPM

must

move

forward on

this very basic

personnel management obligation.

The Centrality

of Performance Appraisal.

In the meantime, the OPM must

manage

the

workforce

it

has.

Before

they

can

reward

or

discipline

federal

employees,

managers

must

first

identify

who

their

top

performers

are

and

who

is

performing

less than

adequately.

In

fact,

as

Ludwig

von

Mises

proved

in

his

classic

Bureaucracy,14 unlike

the

profit-and-loss

evaluation tool

used in

the

private

sector, government

performance

measurement

depends totally

on

a

functioning appraisal

system. If

they

cannot

be

identified

in

the

first place

within a

functioning appraisal

system, it

is impossible

to

reward good

performance or

correct poor

performance. The

problem is that

the

collegial

atmosphere of

a

bureaucracy

in

a

multifaceted appraisal

system

that

is

open

to

appeals

makes this

a

very

challenging ideal

to

implement

successfully. The

GAO reported

more recently

that overly

high and

widely spread

perfor- mance

ratings

were

again

plaguing

the government,

with

more

than

99

percent

of employees

rated fully

successful or above

by their

managers, a mere

0.3 percent

rated as

minimally

successful,

and

0.1

percent

actually

rated

unacceptable.15 Why? It is human

nature that

no one

appreciates

being told

that he

or she

is less

than outstanding in

every

way.

Informing

subordinates

in

a

closely

knit

bureaucracy

that they

are not

performing well is

difficult. Rating compatriots

is even

consid- ered

rude

and

unprofessional.

Moreover,

managers

can

be

and

often

are

accused

of

racial or

sexual discrimination

for

a

poor rating,

and

this

discourages honesty.

In

2018, President

Trump issued

Executive Order

1383916 requiring

agen-

cies to reduce

the time

for employees

to improve

performance before corrective

action could be taken;

to initiate

disciplinary actions against

poorly

performing employees

more expeditiously; to reiterate

that agencies

are obligated

to make

employees improve;

to reduce

the time

for employees

to respond

to allegations

of poor performance; to

mandate that

agencies

remind supervisors

of expiring

employee probationary periods; to prohibit agencies from entering into

settlement agreements

that

modify

an

employee’s

personnel

record;

and

to

reevaluate

proce- dures for

agencies to discipline supervisors who retaliate against

whistleblowers. Unfortunately, the order was overturned by the

Biden Administration,17 so

it will need to be

reintroduced in 2025.

The fact remains

that

meaningfully

evaluating employees’

performance is

a critical part

of

a

manager’s

job.

In

the

Reagan

appraisal

process,

managers

were evaluated

on how

they themselves

rated their

subordinates. This is

critical

to

Mandate

for Leadership:

The

Conservative

Promise

responsibility

and

improved

management. It

is

essential

that political

executives

build policy goals directly into employee appraisals both for mission

success and

for

employees to

know what

is

expected.

Indistinguishable

from

their coworkers on

paper, hard-working

federal employees

often go

unrewarded for

their efforts

and

are often

the system’s

greatest

critics. Federal

workers who

are performing

inadequately get

neither

the

benefit

of

an

honest

appraisal

nor

clear

guidance

on

how

to

improve.

Political

executives

should

take

an

active

role

in

supervising

per-

formance

appraisals

of

career

staff,

not

unduly

delegate

this

responsibility

to

senior

career managers,

and

be

willing

to

reward

and

support

good

performers.

Merit

Pay.

Performance

appraisal means little to daily operations if it is not tied

directly

to

real

consequences

for success

as

well

as

failure.

According

to a

survey

of

major U.S. private

companies—which, unlike the federal government, also have a

profit-and-loss

evaluation—90 percent

use

a

system

of

merit

pay

for

performance

based on

some

type

of

appraisal

system.

Despite

early

efforts

to

institute

merit

pay

throughout

the federal

government,

however,

compensation

is

still

based

primarily on

seniority rather than merit.

Merit

pay

for

executives and

managers was

part of

the

Carter

reforms and

was implemented

early in

the Reagan

presidency. Beginning in

the summer

of 1982,

the

Reagan OPM

entered

18

months

of

negotiations

with

House

and

Senate

staff on

extending

merit

pay

to

the

entire

workforce.

Long and

detailed

talks

between the

OPM and

both Democrats and Republicans

in Congress

ensued, and

a final agreement was reached

in 1983 that supposedly ensured the passage of legislation

creating

a new

Performance

Management

and

Recognition

System

(PMRS)

for

all, (not

just

management) GS-13

through GS-15

employees.

Meanwhile, the OPM issued

regulations to expand the role of performance related to pay

throughout the entire workforce, but congressional allies of the

employee

unions,

led

by

Representative Steny

Hoyer

(D)

of

government

employee– rich

Maryland,

stoutly resisted

this extension of

pay-for-performance

and, with

strong union

support,

used

the

congressional

appropriations

process

to

block

OPM

administrative pay reforms.

Bonuses for SES career employees survived, but per-

formance

appraisals

became

so

high

and

widely

distributed

that

there

was

little

relationship between performance and remuneration.

Ever

since the

original merit

pay

system

for

federal

managers (GM-13

through GM-15

grade

levels, just

below the

SES) was

allowed to

expire in

September 1993,

little to

nothing has been done either to reinstate the federal merit pay

program for managers or to distribute performance rating

evaluations for the SES, much less to extend

the

program

to

the

remainder of

the

workforce.

A

reform-friendly

President

and

Congress

might just

provide the

opportunity to

create a

more comprehensive

performance plan; in the meantime, however, political executives

should use exist-

ing

pay

and

especially

fiscal awards

strategically

to

reward good

performance to

the

degree allowed

by law.

2025

Presidential Transition

Project

Making the

Appeals Process Work. The

nonmilitary government dismissal

rate is

well

below

1

percent,

and

no

private-sector

industry

employee

enjoys

the job

security that

a federal employee

enjoys. Both

safety and

justice demand

that managers

learn

to

act

strategically

to

hire

good

and

fire

poor

performers

legally.

The initial paperwork

required to separate poor or abusive performers (when they

are

infrequently identified)

is

not

overwhelming,

and

managers

might

be

motivated

to act

if

it

were

not

for

the

appeals

and

enforcement

processes.

Formal

appeal

in

the

private sector is mostly a

rather simple two-step process, but government unions and

associations have been able to convince politicians to support a

multiple and extensive appeals and enforcement process.

As noted, there

are multiple

administrative appeals bodies.

The FLRA,

OSC, and

EEOC

have

relatively

narrow

jurisdictions.

Claims

that

an

employee’s

removal or

disciplinary actions violate the terms of a collective

bargaining agreement between

an

agency

and

a

union

are

handled

by

the

FLRA,

employees

who

claim

their

removal

was the

result

of

discrimination

can

appeal

to

the

EEOC,

and

employ-

ees who believe their firing

was retribution for being a whistleblower can go to the

OSC. While

the MSPB

specializes in abuses

of direct

merit system

issues, it

can and

does hear

and

review

almost

any

of

the

matters

heard

by

the

other

agencies.

Cases

involving

race, gender,

religion, age,

pregnancy, disability,

or

national

origin

can

be

appealed

to

the

EEOC or

the

MSPB—and

in

some

cases to

both—and to the

OSC. This

gives employees

multiple opportunities

to

prove

their cases,

and while the

EEOC, MSPB,

FLRA, and

OSC

may

all

apply

essentially the

same burden

of

proof,

the

odds

of

success

may

be

substantially

different

in

each

forum. In

fact,

forum

shopping

among them

for

a

friendlier venue

is

a

common practice,

but

fre-

quent

filers face

no

consequences

for

frivolous

complaints. As

a

result,

meritorious

cases

are

frequently

delayed, denying

relief and

justice to

truly aggrieved

individuals. The MSPB

can and does handle all such matters, but it faces a backlog of

an estimated 3,000

cases of

people who

were

potentially wrongfully terminated

or disciplined as far back as 2013. From 2017–2022 the

MSPB lacked the quorum

required

to

decide

appeals.

On

the

other

hand,

as

of

January

2023,

the

EEOC

had

a

backlog of

42,000

cases.

While

federal employees

win

appeals

relatively

infrequently—MSPB

adminis-

trative

judges

have

upheld

agency

decisions

as

much

as

80

percent of

the

time—the

real

problem is

the time

and paperwork

involved in

the elaborate

process that

managers

must

undergo

during

appeals.

This

keeps

even

the

best

managers

from bringing

cases in

all but

the most

egregious cases

of poor

performance or

mis- conduct. As

a

result,

the

MSPB,

EEOC,

FLRA,

and

OSC

likely

see

very

few

cases compared

to

the

number

of

occurrences, and

nonperformers

continue

to

be

paid and

often are

placed in

nonwork

positions.

Having a choice

of appeals is especially unique to the government. If lower-pri-

ority

issues

were addressed

in-house, serious

adverse actions

would be

less subject

Mandate for

Leadership: The Conservative

Promise

to delay. With the proper limitation

of labor union actions, the FLRA should

have

limited

reason for

appeals.

The

EEOC’s

federal

employee

section

should

be

transferred to

the

MSPB,

and

many

of

the

OCS’s

investigatory

functions

should

be returned to the

OPM. The MSPB could then become the main reviewer of adverse

actions,

greatly simplifying

the burdensome appeal process.

Making

Civil Service

Benefits

Economically and

Administratively Ratio- nal. In recent

years, the combined wages and benefits of the executive branch

civilian workforce totaled $300 billion according to official

data. But even that amount

does

not

properly

account for

billions

in

unfunded

liability

for

retirement and

other

government

reporting

distortions.

Official

data

also

report

employment as

approximately 2 million, but this ignores approximately 20

million contractors

who,

while

not

eligible

for

government

pay

and

benefits,

do

receive

them

indirectly

through contracting

(even

if

they

are

less

generous).

Official

data

also

claim

that national

government

employees

are

paid

less

than

private-sector

employees

are paid

for similar

work, but

several more

neutral sources

demonstrate

that pub-

lic-sector

workers

make

more

on

average

than

their

private-sector

counterparts.

All of this extravagance

deserves close

scrutiny.

Market-Based

Pay and Benefits.

According to current law, federal workers

are

to

be

paid

wages

comparable

to

equivalent

private-sector

workers

rather

than compared

to all

private-sector employees. While

the official

studies claim

that federal

employees are underpaid

relative to

the private sector

by 20

percent or

more,

a

2016

Heritage

Foundation

study

found

that

federal

employees

received

wages that

were

22

percent

higher

than

wages

for

similar

private-sector

workers; if the value

of employee benefits was included, the total compensation

premium for federal employees over their private-sector

equivalents increased to between 30

percent

and 40

percent.18 The

American

Enterprise Institute

found a

14

percent

pay

premium and

a 61

percent total

compensation

premium.19

Base

salary is

only one

component of

a

federal

employee’s total

compensation. In

addition

to

high

starting wages,

federal employees

normally receive

an

annual

cost-of-living

adjustment

(available to all

employees) and generous

scheduled raises known as

step

increases. Moreover, a large

proportion of federal

employ- ees are stationed in the Washington, D.C., area

and other large cities and are entitled

to steep

locality pay

enhancement to

account for

the high

cost of

living in these areas.

A federal

employee with five years’ experience receives 20 vacation days,

13 paid

sick

days, and

all

10

federal holidays

compared to

an

employee

at

a

large private

company

who

receives

13

days

of

vacation

and eight

paid

sick

days.

Federal

health

benefits

are

more

comparable

to those

provided

by

Fortune

500 employers

with

the

government

paying 72

percent

of

the

weighted

average

premiums,

but

this

is

much higher than for most

private plans. Almost half of private firms do not offer

any employer contributions at all.

2025

Presidential Transition

Project

The obvious

solution to these discrepancies is to move closer to a market

model for federal pay and benefits. One need is for a neutral

agency to oversee pay hiring

decisions,

especially for

high-demand occupations.

The

OPM

is

independent

of

agency

operations, so it can assess requirements more neutrally. For

many years,

with

its

Special Pay

Rates program,

the

OPM

evaluated claims

that federal

rates in an

area were

too

low

to

attract

competent employees

and

allowed

agencies to

offer

higher

pay

when

needed rather

than increased

rates for

all. Ideally,

the

OPM

should

establish an

initial pay

schedule for

every occupation

and

region,

monitor turnover

rates and

applicant-to-position

ratios, and

adjust pay

and recruitment

on that basis. Most of this requires legislation, but the OPM should be

an advocate for

a true

equality of

benefits

between the

public and

private

sectors.

Reforming Federal Retirement Benefits.

Career civil servants enjoy retire-

ment

benefits

that are

nearly

unheard

of

in

the

private

sector.

Federal

employees

retire earlier

(normally at age

55 after

30 years),

enjoy richer

pension

annuities, and

receive

automatic

cost-of-living

adjustments

based

on

the

areas

in

which

they retire.

Defined-benefit federal pensions are fully indexed for

inflation—a practice that

is extremely

rare in the private

sector. A

federal

employee with

a preretire- ment income

of $25,000

under the

older of

the two

federal

retirement plans

will receive

at

least

$200,000

more

over

a

20-year

period

than

will

private-sector

work- ers

with the

same

preretirement salary

under historic

inflation levels.

During

the

early

Reagan years,

the

OPM

reformed many

specific provisions

of

the

federal pension

program to

save billions

administratively.

Under

OPM

pres-

sure, Reagan and Congress

ultimately ended the old Civil Service Retirement System

(CSRS)

entirely for

new employees, which (counting

disbursements for the unfunded liability) accounted for 51.3 percent of the

federal government's total payroll. The retirement system that

replaced it—the Federal Employees

Retirement System

(FERS)—reduced the cost of federal employee retirement dis-

bursements

to 28.5

percent

of

payroll

(including

contributions

to

Social

Security

and the

employer

match

to

the

Thrift

Savings

Plan).

More

of

the

pension

cost

was

shifted

to the

employee,

but

the

new

system

was

much

more

equitable

for

the

40 percent

who received

few or

no benefits

under the

old system.

By

1999, more

than half

of

the

federal workforce

was

covered

by

the

new

system,

and

the

government’s per

capita share

of

the

cost (as

the

employer)

was

less

than half

the cost

of the

old system:

20.2 percent

of FERS

payroll vs.

44.3 percent

of CSRS

payroll, representing one of

the largest

examples of

government

savings anywhere.

Although

the government

pension

system

has

become

more

like private

pension systems, it still

remains much more generous, and other means might be

considered in the

future to

move it

even closer

to private

plans.

GSA: Landlord and Contractor Management.

The General Services

Administration

is

best

known

as

the

federal

government’s

landlord—designing,

constructing, managing, and preserving government buildings and

leasing and

Mandate

for Leadership:

The

Conservative

Promise

managing

outside commercial

real estate

contracting with

376.9 million

square feet

of

space.

Obviously, as

its

prime

function, real

estate expertise

is

key

to

the

GSA’s

success. However, the GSA is also the government’s purchasing agent,

connecting federal purchasers with

commercial products and

services in

the private sector

and their personnel

management functions. With contractors performing so many

functions

today,

the

GSA

therefore

becomes

a

de

facto

part

of

governmentwide

personnel management.

The GSA

also manages

the

Presidential

Transition Act (PTA) process,

which also

directly

involves the

OPM. A

recent

proposal would

have

incorporated

the

OPM

and

GSA

(and

OMB).

Fortunately,

this

did

not

take

place

in

that

form,

but

it

would

make

sense

for

GSA

and

OPM

leadership

and staff to

hold regular

meetings to

work through

matters of

common

interest such

as moderating PTA personnel

restrictions and the

relationships between contract and

civil service employees.

Reductions-in-Force.

Reducing the number of federal employees seems an obvious

way to

reduce the

overall expense

of the

civil service,

and many

prior Administrations have attempted to do just this.

Presidents Bill Clinton and

Barack

Obama

began

their

terms,

as

did

Ronald

Reagan

and

Donald

Trump,

by mandating

a

freeze

on

the

hiring

of

new

federal

employees,

but

these

efforts

did not

lead

to

permanent

and substantive

reductions

in

the

number

of

nondefense

federal employees.

First,

it

is

a

challenge

even to

know which

workers to

cut. As

mentioned, there

are 2 million federal employees, but

since budgets have exploded, so has the total number of

personnel with nearly 10 times more federal contractors than

federal employees.

Contractors are less

expensive because they

are not

entitled to

high

government

pensions

or

benefits

and

are

easier

to

fire

and

discipline.

In addition,

millions

of state

government

employees

work

under

federal

grants,

in

effect

administering federal

programs;

these

cannot

be

cut

directly.

Cutting

federal employment

can

be

helpful

and can

provide

a

simple

story

to

average

citizens,

but

cutting

functions,

levels,

funds,

and

grants

is

much

more

important

than

setting simple

employment size.

Simply

reducing

numbers can

actually

increase costs.

OMB

instructions fol-

lowing President Trump’s

employment freeze told

agencies to

consider buyout

programs, encouraging early

retirements in order to shift costs from current bud-

gets

in

agencies

to the

retirement

system

and

minimize

the

number

of

personnel

fired. The

Environmental Protection Agency

immediately implemented such

a program, and OMB

urged the passage of legislation to increase payout maximums

from

$25,000

to

$40,000

to

further

increase

spending

under

the

“cuts.”

President

Clinton’s OMB had introduced

a similar buyout that cost the Treasury $2.8 billion,

mostly

for

those

who were

going

to

retire

anyway. Moreover,

when

a

new

employee

is hired

to

fill

a

job

recently

vacated

in

a

buyout,

the

government

for

a

time

is

paying two

people to fill one job.

2025 Presidential

Transition Project

What is needed

at the

beginning is

a freeze on

all top

career-position hiring to

prevent

“burrowing-in”

by

outgoing

political

appointees.

Moreover,

four

fac-

tors

determine

the order

in

which

employees

are

protected

during

layoffs:

tenure,

veterans’ preference, seniority, and performance in that order

of importance. Despite

several

attempts

in

the

House

of

Representatives

during

the

Trump

years to

enact

legislation that

would

modestly

increase

the

weight

given

to

performance

over time-of-service,

the

fierce

opposition

by

federal

managers

associations

and

unions representing

long-serving but not necessarily well-performing constituents

explains why the bills failed to advance. A determined President

should insist that performance

be first

and be

wary of

costly types

of

reductions-in-force.

Impenetrable

Bureaucracy.

The

GAO

has

identified almost

a

hundred

actions that the

executive branch

or

Congress

could take

to

improve

efficiency and

effec- tiveness across

37 areas that span a broad range of government missions and

functions.

It identified

33

actions

to

address

mission

fragmentation,

overlap,

and duplication

in

the

12

areas

of

defense,

economic

development,

health,

homeland

security, and information

technology. It also identified 59 other opportunities for

executive agencies

or Congress

to reduce

the cost

of government

operations or enhance revenue collection across 25 areas of government.20

A

logical place

to

begin

would be

to

identify

and

eliminate

functions and

pro- grams that

are

duplicated

across Cabinet

departments or

spread across

multiple agencies.

Congress hoped

to help

this effort

by passing

the Government

Perfor- mance and Results Act of 1993,21 which required all federal

agencies to define their

missions,

establish

goals

and

objectives,

and

measure

and

report

their

per- formance

to Congress.

Three decades

of endless

time-consuming

reports later, the government continues

to grow

but with

more paper

and little

change either

in performance

or in

the number

of levels

between

government and

the people.

The Brookings Institution’s Paul

Light emphasizes the importance of the

increasing

number of

levels

between

the

top

heads

of

departments

and

the

people at

the

bottom

who

receive

the products

of

government

decision-making.

He

esti-

mates

that

there

are

perhaps

50

or

more

levels

of

impenetrable bureaucracy

and

no way

other

than

imperfect

performance

appraisals

to

communicate

between

them.22 The

Trump

Administration

proposed some

possible

consolidations, but these

were

not

received

favorably

in

Congress,

whose

approval

is

necessary

for

most

such

proposals.

The best

solution

is

to

cut

functions

and

budgets

and

devolve

respon-

sibilities. That

is a

challenge

primarily for

Presidents, Congress, and

the entire

government, but

the

OPM

still

needs

to

lead

the

way

governmentwide

in

managing

personnel

properly

even in

any

future

smaller government.

Creating a Responsible Career Management Service.

The people elect a

President

who

is

charged

by

Article

2,

Section

3

of

the

Constitution23 with

seeing

that the laws

are “faithfully executed” with his political appointees

democratically

linked

to

that

legitimizing

responsibility.

An

autonomous bureaucracy

has

neither

Mandate for

Leadership: The Conservative

Promise

independent

constitutional status nor separate moral legitimacy. Therefore,

career

civil

servants

by

themselves

should not

lead major

policy changes

and

reforms.

The creation of

the Senior

Executive

Service was

the top

career change

intro- duced by the 1978 Carter–Campbell Civil Service

Reform Act. Its aim was to

professionalize

the

career

service

and

make

it

more

responsible

to

the

democrat-

ically elected commander in

chief and his political appointees while respecting the rights

due

to

career

employees,

very

much

including

those

in

the

top

positions.

The

new

SES

would

allow

management

to be

more

flexible

in

filling

and

reassigning

executive positions

and locations

beyond narrow

specialties

for more

efficient mission

accomplishment and

would

provide

pay

and

large

bonuses

to

motivate career

performance.

The desire to infiltrate political

appointees improperly into the high career

civil

service

has been

widespread

in

every

Administration,

whether

Democrat

or Republican.

Democratic

Administrations,

however,

are

typically

more

successful

because they

require

the

cooperation

of

careerists,

who

generally

lean

heavily

to

the Left. Such burrowing-in

requires career job descriptions for new positions that

closely

mirror

the

functions

of

a

political

appointee;

a

special

hiring

authority

that

allows the bypassing of

veterans’ preference as well as other preference categories;

and the ability

to frustrate

career

candidates from

taking the

desired

position.

President

Reagan’s OPM

began by

limiting such

SES

burrowing-in, arguing that the

proper course

was to

create and

fill political

positions. This simultane-

ously

promotes

the CSRA

principle

of

political

leadership

of

the

bureaucracy

and respects

the

professional autonomy

of the career service.

But this

requires that

career SES

employees

should respect

political

rights too.

Actions such

as career staff

reserving

excessive

numbers

of

key

policy

positions

as

“career

reserved”

to deny

them to

noncareer SES employees

frustrate CSRA intent.

Another

evasion is the general

domination by career staff on SES personnel evaluation boards,

the opposite

of noncareer

executives dominating these

critical

meeting discussions

as

expected

in the

SES.

Career

training

also

often

underplays

the

political

role

in leadership

and inculcates

career-first policy and

value

viewpoints.

Frustrated

with these

activities by

top

career

executives, the

Trump Adminis-

tration

issued

Executive Order 1395724 to make career

professionals in positions

that

are

not

normally

subject to

change

as

a

result

of

a

presidential

transition

but

who

discharge

significant

duties

and

exercise

significant

discretion

in

formulating

and implementing executive

branch policy and programs an exception to the com-

petitive

hiring

rules

and

examinations for

career

positions

under

a

new

Schedule

F.

It

ordered

the

Director

of

OPM

and

agency

heads to

set

procedures

to

prepare

lists of

such confidential, policy-determining, policymaking, or

policy-advocating

positions

and

prepare

procedures to

create exceptions

from civil

service rules

when careerists

hold such

positions, from which

they can

relocate back

to the

regular civil service

after

such

service.

The

order

was

subsequently

reversed

by

President

2025 Presidential

Transition Project

Biden25 at the demand

of the

civil service

associations and unions.

It should

be reinstated, but SES responsibility should come first.

Managing

Personnel in a Union Environment.

Historically, unions were

thought to

be

incompatible

with

government

management.

There

is

a

natural

limit

to the bargaining power of

private-sector unions, but the financial bottom line of

public-sector unions is

not similarly

constrained. If private-sector

unions push

too

hard

a

bargain,

they

can

so

harm

a

company

or

so

reduce

efficiency

that

their

employer

is forced

to

go

out

of

business

and

eliminate

union

jobs

altogether.

There

is

no

such

limit

in

government, which

cannot

go

out

of

business,

so

demands

can

be

excessive

without negatively

affecting

employee

and

union

bottom

lines.

Even

Democratic President

Franklin Roosevelt

considered union

representa- tion

in

the

federal

government to

be

incompatible

with democracy.

Striking and

even

threats

of

bargaining

and

delay

were considered

acts against

the

people

and thus improper.

It

was

not

until

President John

Kennedy that

union representation

in

the

federal government

was

recognized—and

then merely

by

executive

order.

Labor bargaining was not set in statute until the Carter Administration

was forced

by

Congress to

do

so

in

order

to

pass

the

CSRA,

although all

bargaining was

placed under OPM

review.

The CSRA was

able to

maintain strong

management

rights for

the OPM

and agencies and

forbade collective bargaining on pay and benefits as well as

manage- ment

prerogatives. Over

time,

OPM,

FLRA,

and

agencies’

personnel

offices

and courts,

especially

in Democratic

Administrations,

narrowed

management

rights

so that labor bargaining

expanded as management rights contracted. But the man-

agement

rights

are

still

in

statute,

have

been

enforced

by

some

Administrations,

and should

be

enforced

again

by

any

future

OPM

and

agency

managements,

which should

not be

intimidated by union

power.

Rather than

being

daunted,

President Trump issued

three executive

orders:

•

Executive Order 13836,

encouraging agencies to

renegotiate all union

collective

bargaining

agreements

to

ensure

consistency

with

the

law

and respect for

management rights;26

•

Executive Order 13837,

encouraging agencies to

prevent union

representatives

from

using

official

time

preparing

or

pursuing

grievances

or from

engaging in

other union

activity on

government

time;27

and

•

Executive

Order

13839,

encouraging

agencies

both

to

limit

labor

grievances

on removals

from service

or on

challenging performance appraisals

and to

prioritize performance

over

seniority

when

deciding

who

should

be

retained

following

reductions-in-force.28

Mandate for

Leadership: The Conservative

Promise

All

were revoked

by

the

Biden Administration29 and

should

be

reinstated

by

the

next

Administration,

to

include

the

immediate

appointment of

the

FLRA

General Counsel and

reactivation of the Impasses Panel.

Congress should also consider whether public-sector unions are

appropriate in the first

place. The

bipartisan

consensus up until

the middle

of the

20th cen-

tury

held that

these

unions

were

not

compatible

with

constitutional

government.30 After

more

than

half a

century of

experience with

public-sector

union

frustrations

of

good

government management,

it

is

hard to

avoid reaching

the

same

conclusion.

Fully

Staffing the

Ranks of

Political

Appointees. The President

must rely legally

on

his

top

department

and

agency

officials

to

run

the

government

and

on

top White

House

staff

employees

to coordinate

operations

through

regular

Cabinet

and

other

meetings

and communications.

Without

this

political

leadership,

the

career

civil

service

becomes

empowered

to lead

the

executive

branch

without

democratic

legitimacy.

While

many

obstacles

stand

in

his

way,

a

President

is

constitutionally and

statutorily

required

to fill

the

top

political

positions

in

the

executive

branch

both

to

assist

him

and

to

provide

overall legitimacy.

Most Presidents

have had some difficulty obtaining congressional approval of

their

appointees, but

this has

worsened recently.

After the

2016 election,

President

Trump

faced

special

hostility from

the

opposition

party and

the

media

in

getting

his

appointees

confirmed or even

considered by the

Senate. His

early Office

of Presidential

Personnel

(PPO)

did

not

generally

remove

political

appointees

from the

previous

Administration but

instead

relied

mostly

on

prior

political

appoin-

tees and

career

civil

servants

to

run

the

government.

Such

a

reliance

on

holdovers and

bureaucrats led to a lack of agency control and the absolute

refusal of the Acting Attorney

General

from

the

Obama

Administration

to

obey

a

direct

order from the

President.

Under the early PPO, the Trump

Administration appointed fewer political

appointees

in

its

first

few

months

in

office

than

had

been

appointed

in any

recent

presidency,

partly

because

of

historically

high

partisan

congressional

obstructions

but also

because several

officials

announced that

they preferred

fewer political

appointees in the agencies as a

way to cut federal spending. Whatever the reasoning, this

had the effect of

permanently hampering the

rollout of

the new President’s

agenda.

Thus,

in

those

critical

early years,

much

of

the

government

relied

on

senior

careerists and holdover Obama

appointees to carry out the sensitive responsibili- ties

that would

otherwise belong to

the new

President’s appointees.

Fortunately,

the later PPO, OPM, and Senate leadership began to cooperate to

build

a

strong

team to

implement the

President’s personnel

appointment agenda.

Any

new

Administration would be

wise to

learn that

it will

need a

full cadre

of sound

political

appointees

from

the

beginning

if

it

expects

to

direct

this

enormous

federal bureaucracy.

A close

relationship between the

PPO at

the White

House and the

OPM,

coordinating with agency

assistant secretaries of

administration

2025 Presidential

Transition Project

and PPO’s

chosen White House Liaisons and their staff at each agency, is

essential

to

the

management of

this large,

multilevel, resistant,

and

bureaucratic

challenge. If

“personnel

is

policy”

is

to

be

our

general guide,

it

would

make sense

to

give

the

President

direct

supervision

of

the

bureaucracy with

the

OPM

Director available

in his Cabinet.

A

REFORMED

BUREAUCRACY

Today,

the federal

government’s bureaucracy cannot

even meet

its own

civil service

ideals.

The

merit

criteria

of

ability,

knowledge,

and

skills

are

no

longer

the

basis

for

recruitment, selection,

or

advancement,

while

pay

and

benefits

for

com- parable

work

are

substantially above

those

in

the

private

sector.

Retention

is

not based

primarily

on

performance, and

for

the

most

part,

inadequate

performance is

not appraised, corrected, or punished.

The authors have made many

suggestions here that, if implemented, could

bring

that

bureaucracy

more

under

control

and

enable

it

to

work

more

efficiently and

responsibly,

which

is

especially

required

for

the

half

of

civilian

government that

administers its

undeniable

responsibilities for defense

and foreign

affairs. While a better administered central bureaucracy

is crucial for both those and

domestic

responsibilities, the

problem

of

properly

running

the

government

goes beyond

simple

bureaucratic

administration. The

specific

deficiencies of the

fed- eral

bureaucracy—size, levels of organization, inefficiency, expense,

and lack of

responsiveness to political leadership—are rooted in the

progressive ideology that

unelected

experts

can

and

should

be

trusted

to

promote

the

general

welfare

in

just about

every area of social life.

The

Constitution,

however,

reserved a

few

enumerated

powers to

the

federal

government

while leaving

the

great

majority of

domestic activities

to

state,

local, and private

governance. As

James Madison

explained: “The

powers reserved

to the

several States

will extend

to all the objects,

which, in

the ordinary course

of affairs, concern the

lives,

liberties and

properties of

the people;

and the internal order,

improvement and

prosperity of

the state.”31

Modern

progressive

politics has simply given

the national

government more to

do than

the complex

separa- tion-of-powers Constitution allows.

That

progressive system

has

broken

down in

our

time,

and

the

only real

solution

is

for

the

national government

to

do

less: to

decentralize and

privatize as

much as

possible

and

then

ensure that

the

remaining

bureaucracy is

managed effectively

along

the lines

of the

enduring

principles set out

in detail

here.

![]()

AUTHORS’ NOTE:

The

authors are

grateful for

the

collaborative work of

the

individuals listed

as

contributors to

this

chapter

for

the

2025

Presidential

Transition

Project.

The

authors

alone

assume

responsibility

for

the

content

of this

chapter, and no

views

expressed herein

should be

attributed to

any other

individual.

Mandate for

Leadership: The Conservative

Promise

ENDNOTES

1.

U.S.

Constitution, Article II, Section 2,

https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/articleii#section1 (accessed February 1, 2023).

2.

5 U.S. Code §§ 1101

et seq. and 1103(a)(5),

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/5/part-II/chapter-11 (accessed February

1,

2023).

3.

5

U.S.

Code

§

1201,

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/5/1201

(accessed

February

1,

2023).

4.

5

U.S.

Code

§

7101,

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/5/7101

(accessed

February

1,

2023),

and

§

7117,

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/5/7117

(accessed

February

1,

2023).

5.

S. 1871, An

Act to Prevent Pernicious Political Activities, Public Law No.

76-252, August 2, 1939,

https://

govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/53/STATUTE-53-Pg1147.pdf (accessed February 1, 2023).

6.

H.R.

995,

Uniformed

Services

Employment

and

Reemployment

Rights

Act

of

1994,

Public

Law

No.

103-353,

101st

Congress,

October 13,

1994,

https://www.congress.gov/103/statute/STATUTE-108/STATUTE-108-Pg3149.

pdf

(accessed

February

1,

2023).

7.

5

U.S.

Code

§

1206,

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/5/1206

(accessed

February

1,

2023).

8.

42

U.S.

Code

§

2000e,

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/2000e

(accessed

February

1,

2023).

9.

40

U.S.

Code

§

581,

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/40/581

(accessed

February

1,

2023).

10.

U.S.

National

Archives,

“Milestone

Documents:

Pendleton

Act

(1883),”

last

reviewed

February

8,

2022,

https://

www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/pendleton-act

(accessed February 2, 2023).

11.

S.

2640,

Civil

Service

Reform

Act

of

1978,

Public Law

No.

95-454,

95th

Congress,

October 13,

1978,

https://